“All aboard the Hollywood merry-go-round — where the wheel of fate spins the stars to fame, to shame, to love or fortune, and where it stops, nobody knows” (Earl Leaf, Hollywood Screen Parade, March 1959). Such was the ride promised by those unabashedly cheesy rags that for filmdom’s first half century functioned as a crucial if unofficial publicity arm for the studios.

Fan magazines offered the most accessible means by which movie lovers could refresh the thrilling images they witnessed on the big screen. Though often vacuous and always riddled with untruths, fan mags masterfully stoked readers’ belief in a hyper-romanticized yet grueling Hollywood milieu whose inhabitants’ lives were at once ordinary and unique, fabulous and tedious, fulfilling and tortured, abundant and deprived.

Readers learned that, at eighteen, Natalie Wood already had “the Thunderbird, the pool, the ermine jacket” (Modern Screen, Feb 1957). But then she married Robert Wagner and learned to make a great hamburger (“All Nat Talks about Is Pots and Pans and Bob,” Photoplay, Feb 1959). Kim Novak, a “reigning Hollywood queen… born to the purple” (Photoplay, Nov 1956), nevertheless lived in a “small, frightened world in which she is the prisoner and jailer both” (Hollywood Screen Parade, March 1959). Talk to folks who knew Cary Grant, “on the surface the most charming, amiable guy in the whole world,” and you were “likely to come away a little staggered — convinced that only Sherlock Holmes or Sigmund Freud could possibly solve the curious case of the complex Cary” (Screen Album, July 1963).

And then there was Liz, undisputed ruler of the fan magazine universe across several decades. With four marriages in the 1950s alone, Elizabeth Taylor shattered almost every cultural more in Eisenhower’s America. She stole Eddie Fisher from wholesome, demure Debbie Reynolds. She abandoned her Christian heritage for Judaism. She swore like a sailor — and ate and drank like one, too. Within three years of marrying Fisher she carried on an affair so passionately public she was condemned on the floor of Congress. Yet the fan magazines put it this way:

The thing to remember about Elizabeth Taylor is not her morals — or lack of them, but that she has dared to keep on hoping for the love she once dreamed of. In a strange way she has become a kind of symbol for all of those who dare to dream. Even though her dream be warped, and the love she wants does not exist, she dreams on. She is a victim of passion which she cannot control. A passion called love. Movies are made about this passion, books and poems are written about it, and Elizabeth Taylor lives it. (“The Mystery of a Woman’s Love,” Movie World, Mar 1964)

The fan mags marketed a moral compass of convenience that substituted ticket sales for true north. To preserve stars’ box office appeal they ignored or actively excused a multitude of bad behavior, from battery to binge drinking to sex with minors. Yet they didn’t hesitate to criticize perceived sins — as long as such criticism met the needs of movie moguls like Jack Warner, Louie B Mayer or Harry Cohn. For example, the storybook marriage of popular stars Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh exploded in the early ‘60s, when Curtis took up with his underage Taras Bulba co-star, Christine Kaufmann. With Curtis by then the bigger box office draw, salvaging his reputation was the studios’ priority, and jilted Janet became fair game. Christine, the fan mags claimed, was actually “more mature” than twice-as-old Curtis. “She was never 17 or 18 in the American sense of the word” (Screen Stars, Feb 1964), and “from the very beginning of the relationship, it was Christine who took the lead and assumed the role of teacher” (Screen Album, July 1963).

On the other hand Leigh was chastised for immature, unglamorous behavior. The editors of Movie TV Secrets (Apr 1962) noted approvingly that a headwaiter had recently “dismissed” a barefoot Janet from the dance floor of “the elegant El Morocco,” informing her “she could not dance without her shoes on.” The editors expressed hope “that more niteries will see fit to follow th[is] example.” According to the column, “The most sought after movie personalities are Liz Taylor, Natalie Wood, Troy Donahue, and Frank Sinatra. They got that way by being glamorous.” About the time this object lesson was published, Mrs. Eddie Fisher was carrying on with also-married Richard Burton; Nat was divorcing Bob Wagner for (then) undisclosed (but decidedly salacious) behavior; Troy was settling a lawsuit over the claim he punched out his ex-fiancée, Lili Kardell; and Sinatra was banished from Kennedy’s Camelot thanks to his alleged connection to mobster Sam Giancana.

* Definition of Hollywood by columnist Sidney Skolsky (Photoplay, Aug 1964): “A place where no matter what you hear about it, it’s true.”

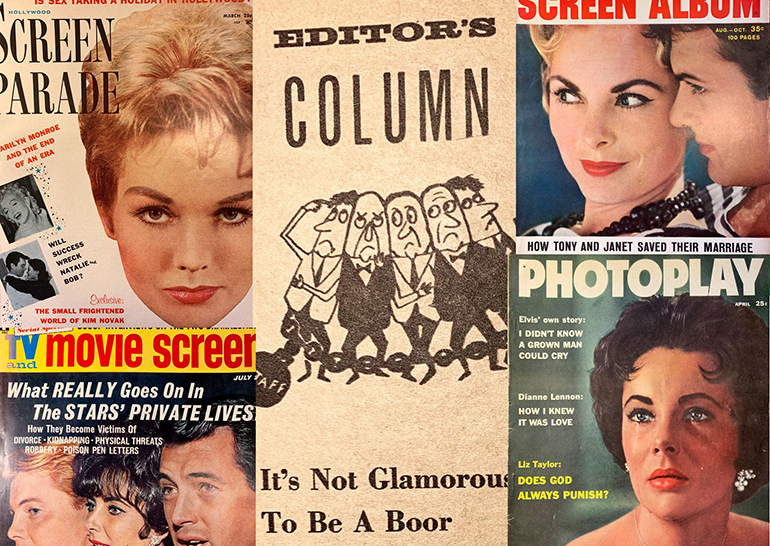

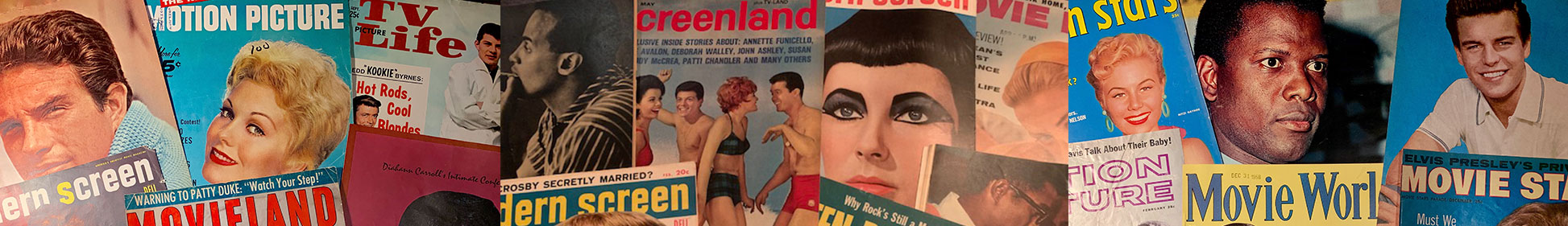

Image credits, clockwise from upper left: (1) Hollywood Screen Parade Mar 1959; (2) Photoplay Apr 1960; (3) Movie TV Secrets Apr 1962; (4) TV and Movie Screen July 1962; (5) Modern Screen June 1964.

Meta Hollywood! What a great idea!