“The idea of a star being born is bushwah. We could make silk purses out of sow’s ears every day in the week.” So bragged studio mogul Louis B. Mayer (quoted by Jeanine Basinger, The Star Machine, 2007). Up to a point, Mayer was right: Hollywood in the studio era was a factory town whose production line turned out not just movies and TV series but stars. As Basinger observes in the very first sentence of her terrific study of starmaking, “It’s a crackpot business that sets out to manufacture a product it can’t even define, but that was old Hollywood.”

The industry employed networks of agents and scouts to extract its raw material from the nation’s beauty contests, amateur theatricals, high school yearbooks and drugstore counters. Then a phalanx of stylists, nutritionists, voice, dance and decorum coaches, dentists and plastic surgeons went to work, shaping their subjects into images both fresh and familiar — the next John Wayne or Lana Turner. Reporter Bill Davidson explains in his Hollywood tell-all (The Real and the Unreal, 1961), “The creation of a movie star often is an artificial process, not unlike the manufacture of Cheddar cheese.”

For the most part, the stars themselves understood their processed nature. Elizabeth Taylor once said to Davidson, “I’m the same as a key piece of machinery in a steel mill.” Even more blunt, Kim Novak told the press that Columbia Studios head Harry Cohn — who died after a series of heart attacks that some insiders credited to Novak’s alleged romance with Sammy Davis Jr. — “said I was nothing but a piece of meat in a butcher shop. Harry Cohn packaged me like sausage” (quoted in Peter Harry Brown, Kim Novak: Reluctant Goddess, 1986).

The fan magazines had their roles in the production line, fostering the constant demand for new discoveries and engendering hope that an aspiring star in Skokie or Long Island might be among them. A feature on Shelley Winters (Motion Picture, Aug 1951) described to hopeful readers how that might happen: “A girl is spotted at the ribbon counter of The Bon Ton or The Boston Store, she’s given a screen test and whisked off to Hollywood, and a year later she’s the most glamorous thing on film. She lives in a mansion, she dines at Romanoff’s, she wears Adrian originals, and every time she extends a lacquered hand to an eligible Hollywood male, it makes every column and broadcast emanating from the cinema city. She is a movie star.”

And it did happen, as the fan mags were quick to highlight. Columnist Rona Barrett (Motion Picture, Nov 1962) gave this account of the discovery of drop-dead gorgeous twins Dack and Dirk Rambo, then appearing on television in Loretta Young’s anthology series: “We keep hearing that Loretta found them in church. We hate to disagree, but nearly three years ago, Troy Donahue’s ex-girlfriend, Nan Morris, and yours truly found them in Ben Frank’s, an eatery on the Sunset Strip.” Back then, Barrett explained, “their names were Norman and Orman Rambo and they were two delightful youngsters from Earlimart, California, just in Los Angeles with some friends for a merry weekend. It was Nan who saw their potential as possible recording and movie stars.”

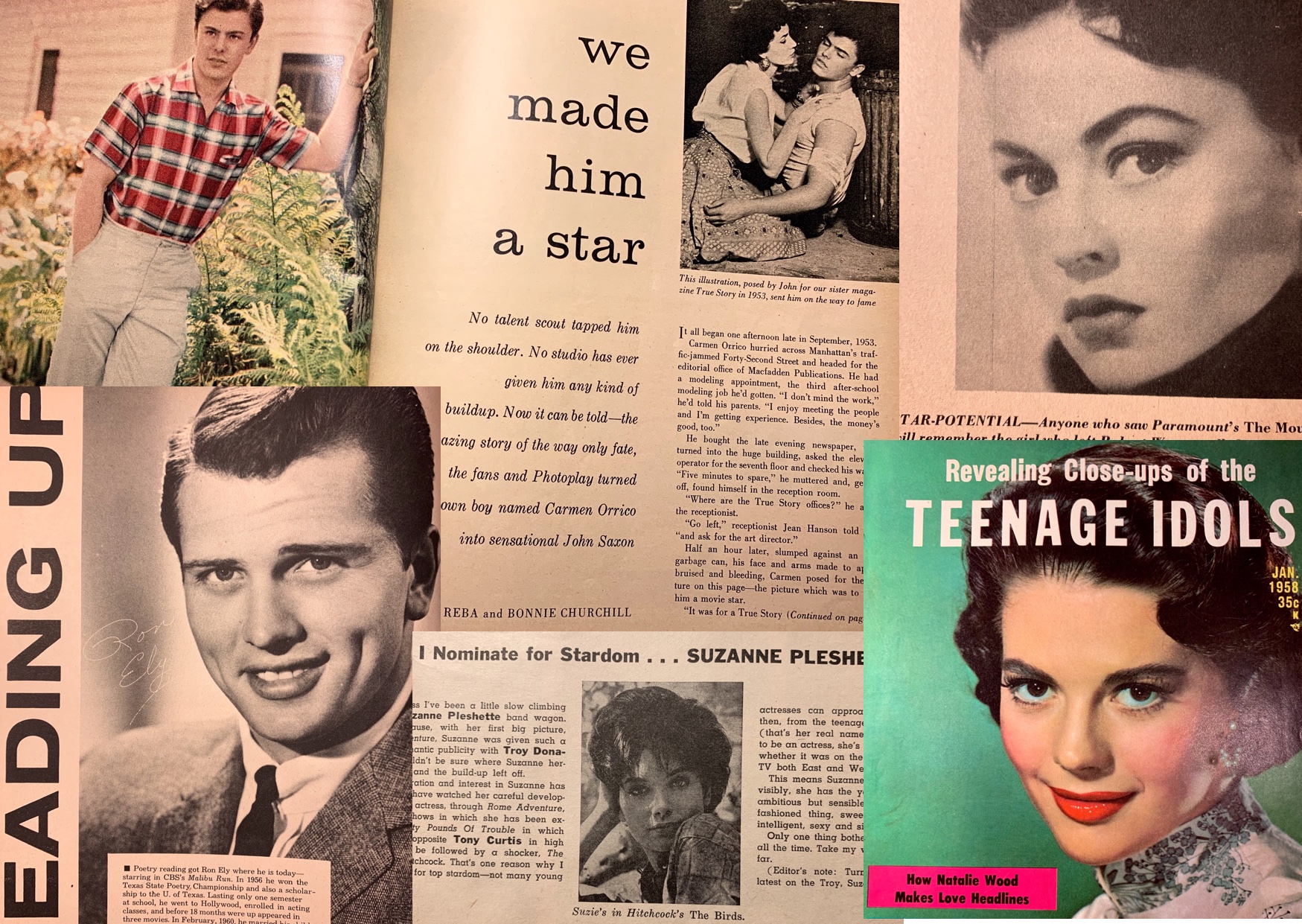

Though magazines reserved most of their space for established stars, almost all gave regular attention to newcomers, such as Movieland and TV Time’s “Star of Tomorrow” blurbs, or Screen Life’s “Newcomer of the Month.” In her monthly column for Modern Screen Louella Parsons included a profile, “I Nominate for Stardom…” Parsons’ predictions hit the mark somewhat more often than others’, but few up-and-comers managed to maintain a foothold in the climb to stardom. For example, how many among those “Heading Up” in 1961 (Movie Stars, Sep 1961) were on your fan radar: Fabian? probably; Ron Ely? perhaps… but Edson Stroll? Toby Michaels? Or among the “Faces for ‘58” (Revealing Close-Ups of the Teenage Idols, Jan 1958): Jean Seberg; Luana Patten; Lisa Davis, a “shapely British import”; Barbara Darrow, who appeared in The Mountain with Robert Wagner; and Carroll Baker? Ironically, the latter feature expressed ambivalence only about Baker’s future, worrying that without “proper roles” (read: less sensationalistic than that of Baby Doll), “she could be a half-forgotten face by year’s end.”

In promoting potential new stars, both the studios and the fan magazines sought to slot them into familiar types. Sharon Hugueny, for example, was among many starlets touted as the next Liz Taylor (Motion Picture, Aug 1962). Suzanne Pleshette was a “new” Natalie Wood (Movie Life, Nov 1962), while Inger Stevens and Dana Wynter competed to be the next Grace Kelly (Mike Connolly, Screen Stories, Oct 1957; “Mr. X Reports,” Movie Life, May 1956). In his autobiography (Tab Hunter Confidential, 2005), Tab Hunter says Edd “Kookie” Byrnes was the first of the “next Tab Hunters,” followed by Troy Donahue — who also was briefly characterized as the next “Kookie” (“Hollywood Dateline,” Movie Life, March 1960). Such typecasting proved so ubiquitous that columnist Sidney Skolsky inquired, “Why is it that most of the movies’ new faces look like the old faces?” (Photoplay, Oct 1957).

The system, and Mayer’s “silk purse” claim, had only one flaw. The performers who reached the heights of stardom, who made indelible impressions on the moviegoing public no matter how extended — like Grant or Turner — or how brief — like Harlow or Grace Kelly — their careers before the camera, all had an elusive something the studios couldn’t manufacture. Fan mag features (along with all of Hollywood) repeatedly sought to define it: “There is no star, male or female, of any stature in Hollywood, who doesn’t have a magnetic, vibrant personality. It might be one that sets your teeth on edge; it might be one that makes the lady columnists get out their vendetta’s and axes, as was the case with Lana Turner at the height of her fame, but they all have it. It’s in their eyes, it’s a sense of almost animal vitality” (Marion Lord, Hollywood Screen Parade, March 1959). The word “magnetism” (and its variations) inevitably cropped up: “On the stage, acting is everything. On the screen, it’s personality that counts. Physical magnetism. ‘Flesh impact.’ Acting ability is frosting on the cake. Sure, a few hardy souls like Bette Davis have forced the screen to accept acting talent. But brilliant actress that she is, Davis also had camera magnetism. Those popping eyes and restless, cigarette-waving hands were made for the camera; they moved” (Lawrence J. Quirk, Screen Stars, June 1965).

Despite these efforts — and countless others — Jeanine Basinger argues that nobody, past or present, “can define what a movie star is except by specific example.” The closest you can come is “a variation of Justice Potter Stewart’s famous remark about pornography: ‘I know it when I see it’” (The Star Machine, 2007). My own personal example, though it pains me somewhat to say it, is this: Natalie Wood was a star; Suzanne Pleshette was an actress. Like Wood, Pleshette was gifted with abundant beauty and talent. Especially in television, especially in comedic parts, she also had a certain charisma before the camera. She played roles originally planned for Wood — naïve Prudence Bell in Rome Adventure, the nymphomaniac Grace Caldwell in A Rage to Live — and came close to landing the Broadway role of Gypsy Rose Lee, which Wood famously played on film. But she lacked Wood’s “love affair with the camera,”* and she never ignited viewers’ hearts and imaginations as Wood did.

In the end, as Basinger concludes, it’s the moviegoers, the fan magazine readers who determine the fate of those “Faces of ’58.” And “what can finally be said about the creation of movie stars is simply this: it’s a mysterious process” (Basinger, American Cinema: One Hundred Years of Filmmaking, 1994).

* In the biography, Natasha (reissued this year as Natalie) by Suzanne Finstad (2001, 2020), Debbie Reynolds is quoted as saying about Wood, “The camera loved her. She had features for the camera like Elizabeth Taylor and Marilyn Monroe. They were so beautiful, and the camera loved their faces! It was a love affair with the camera, and Natalie had that.”

Image credits, clockwise from upper left: (1) Photoplay Oct 1957; (2) Revealing Close-Ups of the Teenage Idols Jan 1958; (3) Revealing… again; (4) Modern Screen Feb 1963; (5) Movie Stars Sep 1961.

Love how gracefully & pithily you weave the bits together.