We tend to think of fans as obsessed with a gorgeous object of desire, calling up images of young girls swooning over Elvis or the Farrah Fawcett pinup on every pubescent boy’s wall in 1976. But for fan magazine readers, the stars they followed were as much subject as object — the fantasy readers wanted to live as much as the passion they sought to embrace.

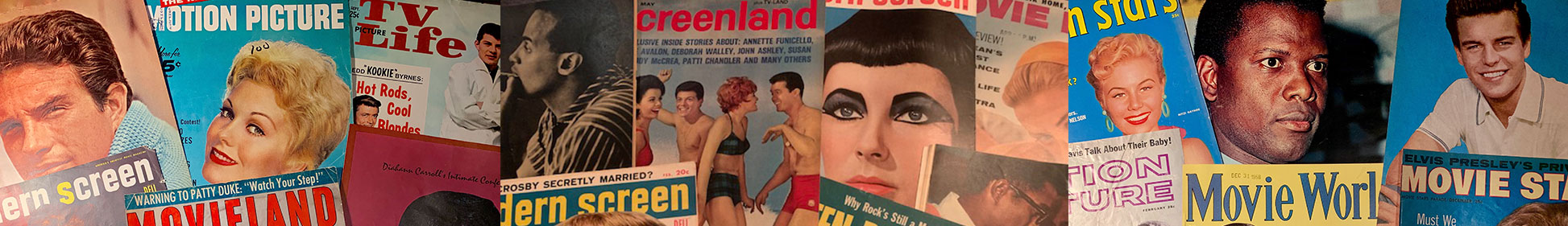

Fan mags played to these fantasies with craft and precision. Though the vast majority of readers were female, cover images featured women far more often than hunky male heartthrobs. And — except for Liz, compelling through joy, tragedy and scandal alike — the stars typically gracing the covers were not unruly sex symbols like Marilyn or the ever-trashy Jayne Mansfield, who invented the wardrobe malfunction decades before Janet Jackson. Rather, cover stars were the kinds of women with whom readers could readily identify: “good girls” like Sandra Dee or Debbie “They’d laugh if I tried to be sexy!” Reynolds (Movie Mirror, Nov 1960). Or the vulnerable and long-suffering, like Connie Stevens, whose photo captions tended along the lines of, “Every book of love needs a chapter on heartbreak. And nobody’s better qualified to write it than Connie” (Screen Stars Album No 3, 1963). Or wives and widows like Janet Leigh and Jackie Kennedy, the latter billed as “America’s newest star” in the October 1961 Photoplay.

For an audience of wannabe cover girls, it was essential not only to reinforce the desirability of becoming the next Doris Day or Connie Stevens, but to offer hope that such a miracle might actually be possible. We could become stars even if we were plain or plump and had never graced a stage or acting class; studio artists and technicians would have a solution for every blemish or missing tooth or talent. Fan magazines told us so, in “insider” features that revealed the hidden mechanics of Hollywood and in catty tidbits in the gossip columns: “Shouldn’t there be some sort of award for Natalie Wood’s voice ghosts in West Side Story? Two people sang for her, one for the high notes, one for the low. And another did her sobbing” (Sheilah Graham, Silver Screen, June 1962).

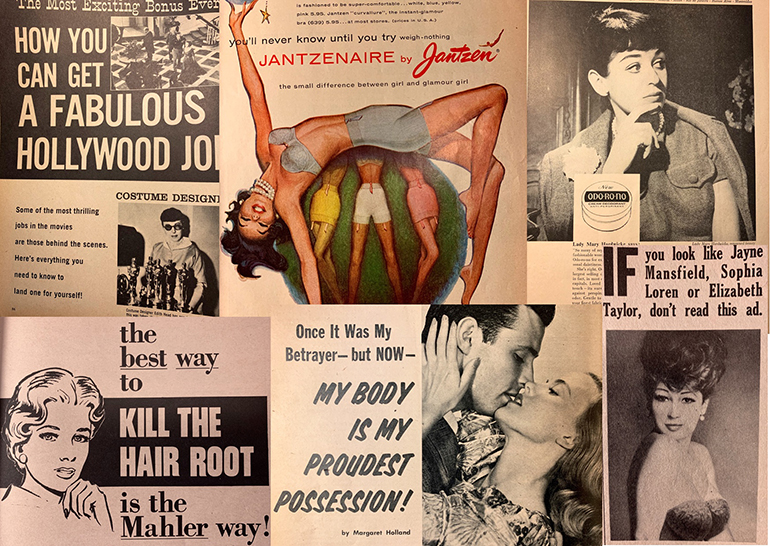

Readers were urged to begin our transformation at home. In fact, coverage about becoming a star almost always segued into tips for becoming as beautiful as a star, a sleight of hand that finessed the issue of actually having to launch a career. The November 1960 cover of Movie Mirror advertised a “Special Bonus” section, “How you can become a movie star!” but the article’s opening paragraph accomplishes the bait-and-switch: “Want to be as beautiful as your top favorites? The stars show you it’s not impossible if you follow just one rule — work on it!”

The magazines peddled an array of strategies and products through which readers could work on it. Articles in Movie Mirror’s special feature revealed how to dress like the stars (Debbie Reynolds: “I adore crazy colors but subdue my passion for them by wearing them combined with black, navy or grey”); how to do your hair like the stars (Kim Novak: “I have a soft permanent every two months, use an oil shampoo twice a week, and set my hair nightly in stand-up pin curls on top, flat pin curls on the side and back”); and how to lose weight like the stars (Mitzi Gaynor: “I used to be a blimp but lost weight quickly on this sure-fire diet: breakfast: half grapefruit, two soft-boiled eggs, skimmed milk; lunch: lean hamburger or small serving chicken, green vegetables, tablespoon cottage cheese; dinner: small steak, tomatoes or spinach”).

Ads offered solutions for almost any barrier to beauty. Books and pamphlets sold tips for losing or gaining weight, slimming down fat legs or building up skinny ones. A cornucopia of creams could be ordered to enhance a woman’s allure. Zonite promised “internal cleanliness” while Arrid promised protection from “sex perspiration” and Pro-Forma, with “extract of Galega” (from France, of course) promised “fuller, firmer bosoms” (Motion Picture, Aug 1962). Her Highness Hormone Cream, with “10,000 units of Estradiol and other beneficial substances… fills your hope chest, revives dreams of beauty, and heightens your charms,” though its precise function is never identified (Movie Mirror, Nov 1964).

There were also assistive devices — not just wigs, bras, corsets, girdles and hernia supports such as the Rupture-Easer (Movie Mirror, Nov 1958), but more imaginative items as well. The “Amazing New Abdo-Slim” was a hybrid of girdle and corset, with an “extra fly front feature which completely hides the laces so they can’t be seen even through the sheerest dresses” (Inside Movie, April 1965). The Firmatron, one of the few devices not available by mail order, could be “operated only by a specially trained salon technician” who “either uses pads or wears gloves directly wired to the machine to apply impulses [that] activate and exercise both the voluntary and involuntary muscles of the face and neck” (Movie TV Secrets, April 1962).

For those readers for whom working on it couldn’t get us near enough to Hollywood’s standards for desirable womanhood — women with the wrong skin color, women who were too mannish or misshapen or old — the magazines offered options as well. Ads for vocational opportunities and money-making schemes abounded. Readers could sign on as the “Mason Shoe Counselor in your town” or sell children’s records or Christmas cards. Ads touted “$200 monthly possible, sewing Babywear!” or “$75 weekly possible preparing mail (details 10 cents)” (TV & Movie Album Vol 6, 1963).

Vocational skills were recommended even for those readers who intended to pursue a career in Hollywood. Ahead of recommendations for a resume, a “book on the technical aspects of television,” courage, determination, head shots and “a well-developed sense of fashion and grooming,” one magazine’s “complete kit” for becoming a TV star listed “a certificate showing you have mastered secretarial skills.” The first step toward fame, the article noted, was to go to a local television station “and try for a job as anything. Your industriousness, sincerity, interest will get you promoted.” The article made no guarantees of success: “Not all make it… but don’t be discouraged and look upon it all as a wonderful experience. You’ll have a great time if nothing else. Good Luck!” (TV & Movie Album, Vol 6, 1963).

Image credits, clockwise from upper left: (1) Movie Screen Yearbook No. 9, 1962; (2) Photoplay Oct 1957; (3) Photoplay July 1960; (4) Movie Stars Nov 1964; (5) Ad for “Slimtown” weight loss program, Silver Screen Apr 1959; (6) Movie World July 1964.

Like!! Thank you for publishing this awesome article.