Before the advent of video and digital media, film images were elusive. Thrilling movies and gorgeous stars might imprint themselves on our imagination, but to refresh those mental pictures we were forced to wait for a re-release or the channel 4 late movie. Fan magazines provided visuals to which we could return again and again, and fleshed out our fantasies about the stars. Though much of what the magazines printed fell far short of reality, readers didn’t particularly care. We wanted to be entertained; more, we wanted to be taken inside our own dreams. The fan mags told lies we wanted to hear and, along the way, helped shape our ideas about love, beauty, happiness, success and moral behavior.

This blog focuses on the fan mags of the 1950s and early to mid 1960s, the last period in which the studio star system and the Hollywood mass media operated (more or less) in sync. The studios were in decline and with them the moguls’ legions of media fixers and fabulators. At the same time the rise of television and tabloid celebrity journalism fostered a market for the very kinds of scandal the Hollywood machinery had long worked to suppress. Fan magazines had to get more and more creative – and contradictory – to simultaneously meet the moguls’ demands and feed the public’s growing appetite for scandal. By the 1970s these clashing motives overwhelmed the genre; most fan magazines failed to survive the decade.

But they left behind generations whose romantic fantasies, self-image and beliefs about fame, fortune and true love were shaped not only by what they experienced at the movies but by what they saw in the pages of Photoplay, Modern Screen and dozens of others. The magazines also left a folklore of sorts, fables and life lessons about the stars, some of which resonate today. Also left to us is a vast, largely unexplored literature complete with its own vocabulary, syntax and stylistic conventions. This blog seeks to explore these legacies.

Though the blog is not intended as an academic work, I apply ethical research methods, citing sources; avoiding — or at least making explicit — assumptions; and developing a body of evidence for the information presented. The problem of evidence in this context is that, as Peter Biskind (Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, 1998) has written, “Hollywood is a town of fabulators” — a place where “very little of what matters is committed to paper” and where fiction extends beyond the page or screen into the lives of its inhabitants. This was certainly true in the Fifties and Sixties, when not only stars’ names but their histories and current affairs were often creative acts. The studios assiduously suppressed scandals; they also sometimes invented them, as a way of correcting or punishing a recalcitrant employee. (See Tab Hunter’s 2005 memoir, Confidential, for a notable example.)

Who for instance can say with certainty that Doris Day had an affair with Dodgers baseball star Maury Wills in 1962, or Kim Novak with Sammy Davis Jr. a few years earlier? Or whether Marilyn Monroe telephoned Peter Lawford or Bobby Kennedy the night she died? Each of these events was hinted at in the fan magazines of the day; all have been presented as fact — and denied as fiction — in other venues. Read enough fan features and gossip columns of the day and you often begin to get a feel for what seems true, but it’s only that, a feeling. Perhaps by necessity, my interest lies less in presenting the real story than in exploring the myriad told stories with their messy, sometimes ludicrous but often enlightening, always entertaining, contradictions.

Sometimes, though, the real story matters even when the parties involved are no longer alive. Yesterday’s struggles — or failures — to speak truth to power, as the saying goes, can inspire or discourage us today. I do my best, then, to be, as columnist Larry Quirk characterized his “Hollywood-New York Sidelights,” “the gossip column with guts.”

About the Author

I am a writer and pop culture buff, a believer in director Douglas Sirk’s observation that

I am a writer and pop culture buff, a believer in director Douglas Sirk’s observation that

There is a very short distance between high art and trash, and trash that contains the element of craziness is by this quality nearer to art. (Quoted in Sam Kashner and Jennifer MacNair, The Bad and the Beautiful: Hollywood in the Fifties, 2002)

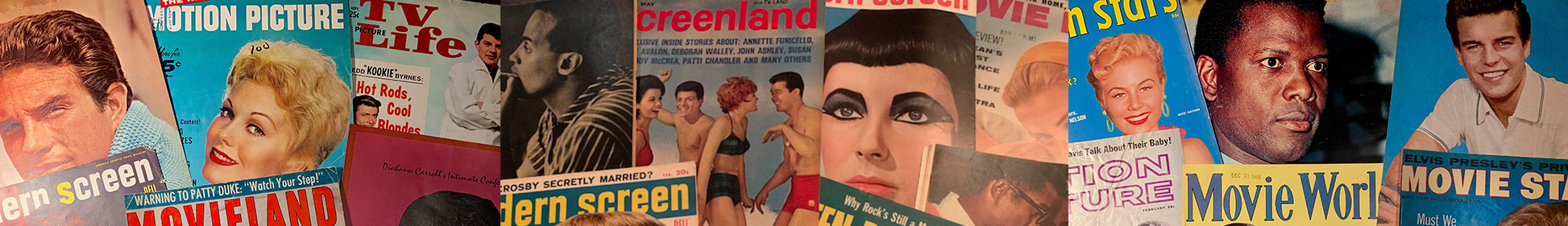

I spent the Saturdays of my childhood at the Cole Theater in Hallettsville, Texas, often sitting through the feature twice to hold onto its magic as long as possible. In 1961 I watched Troy Donahue and Suzanne Pleshette fall in love in Rome Adventure, a schlocky mess of a film but romantically thrilling for dreamy-eyed barely teens like me. From then on I followed Troy and Suzy’s (supposedly) true-life romance in the fan magazines, purchased from Hruzek’s Drugs on the town square. I have what is likely one of the largest assemblages of Suzanne Pleshette memorabilia in the world, as well as a collection of 300+ fan magazines, primarily from the mid-1950s through the mid-1960s, from which I’ve drawn the material for this blog.