NOTE: Given current events, in which — as someone just posted on FB — nature’s being all sweet and pretty after trying to kill many of us just a few days ago, HfOH is delaying our follow-up to last month’s blog in favor of the timely topic of Hollywood weather.

Though the U.S. film industry was born on the East coast, it quickly migrated west; by 1918, more than 80 percent of all movies were made in Southern California. Why? Because Hollywood and its surrounding neighborhoods, located in a dry subtropical climate zone and nestled protectively between mountains and sea, had “nearly perfect weather” (Gregory Paul Williams, The Story of Hollywood, 2005). It offered filmmakers hour upon hour, day after day of precious natural light, including the capacity to film outdoors “even in the dead of winter” (Neil Gabler, An Empire of Their Own, 1988).

But, its new residents soon learned, this ideal moviemaking environment also featured a dramatic propensity for natural disaster: drought, earthquakes, wildfires, mudslides, floods. Not even Hollywood’s biggest stars were immune to real-life, weather-induced calamities. One of the most memorable of these took place at midcentury, and the fan magazines were right there with the weather report.

It started with a severe Southern California drought. Hedda Hopper noted (Motion Picture, Aug 1961), “More rain fell in the Sahara Desert during the past year than we had in Hollywood. Our hill dwellers keep their fingers crossed as most of them have had close calls from forest fires. The wells became so low in the Malibu hill area that salt water seeped in from the ocean. Angela Lansbury tells me they’re rationed on water in the Malibu district and have been since winter’s end. Mrs. Sam Zimbalist, her next door neighbor, has been burned out twice. Angela can’t run the expensive watering system she had installed, so she has to stand by and watch two acres of garden die.”

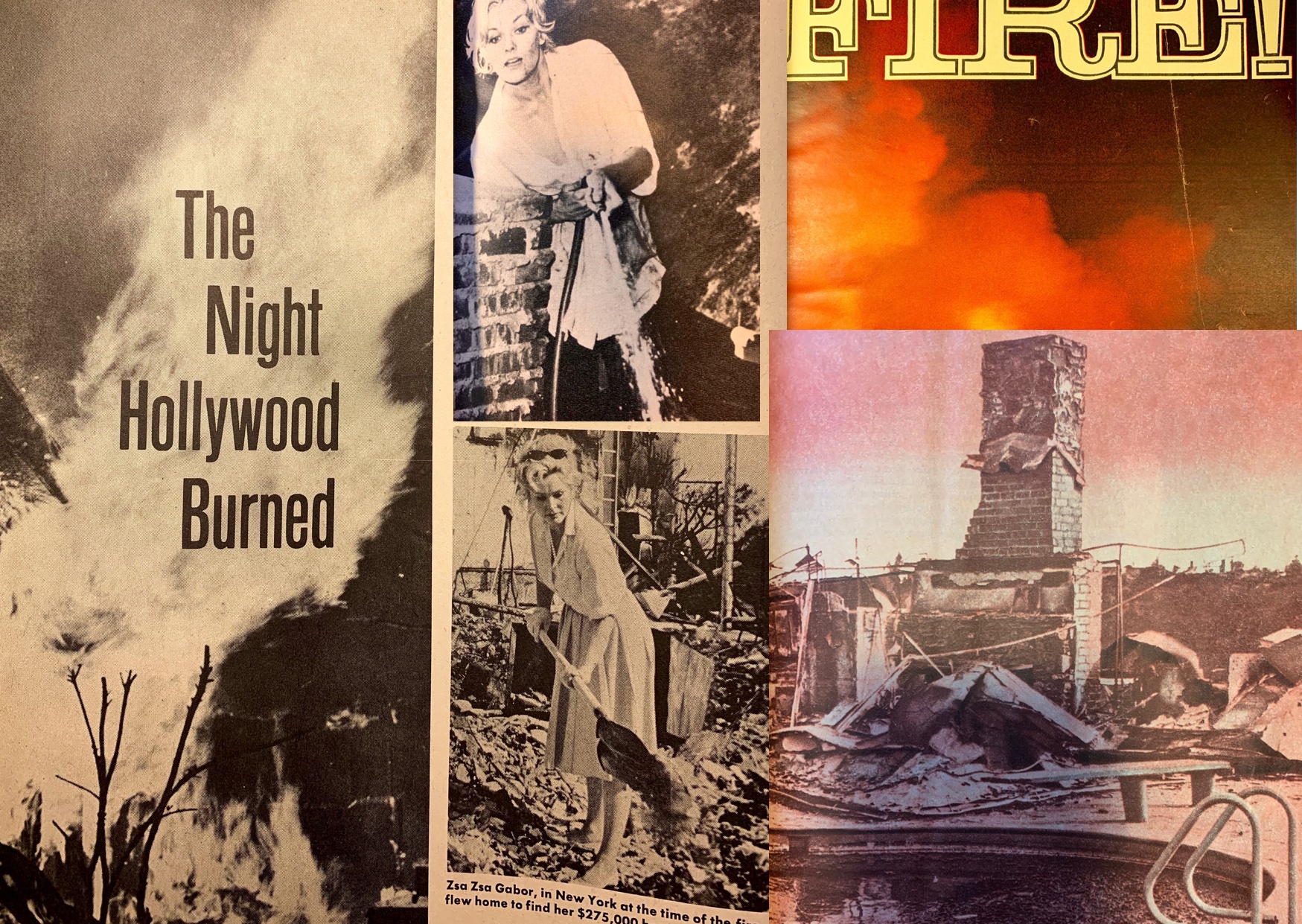

Water rationing and dying gardens soon became relatively minor concerns when the drought — as feared — led to a devastating wildfire in November 1961. In a feature called “Hollywood Inferno!” Movie Stars (Feb 1962) reported: “The worst fire in California history burst down the south slope of the Santa Monica mountains just after dawn on November 6th. By eight o’clock, it had leaped across fashionable Mulholland Drive and was racing down Stone Canyon. Whipping up its own firestorm winds of almost 100 miles an hour, it was raging out of control at 8:33 and by nine o’clock, frantic fire officials had labelled all of Bel Air a disaster area.”

“Worst fire in California history” may sound like typical fan mag hyperbole, but according to the Los Angeles Almanac, the Bel Air-Brentwood fire remains the third most destructive in county history, at least in terms of the number of homes and other structures destroyed. Louella Parsons (Modern Screen, Feb 1962) wrote, “Acre after acre, the streets of Bel-Air and neighboring districts lay as devastated as though a bomb had dropped.” Stars whose homes burned included Burt Lancaster, Fred MacMurray, Joe E. Brown, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Joan Fontaine and Hazel star Don DeFore, among others. “LaVerne Andrews, of the singing Andrews Sisters, saved her valuable collection of old silver by throwing every last piece of it in the swimming pool! Not a shred was left of her house!”

With the help of her then-boyfriend, director Richard Quine, Kim Novak managed to save her home: “Together, they climbed to the flat roof of her home. Side by side, as the hours ticked by, they kept hosing down the roof of Kim’s home. They even managed to check the flames that started on two neighboring homes” (Photoplay, Feb 1962). Ida Lupino and her husband, Howard Duff, did the same, but it was a photo of Novak, on her roof with a hose, face smeared with mud or ashes, that circulated widely, first in newspapers and then in the fan magazines, along with a pic of Zsa Zsa Gabor digging through the rubble of her home with a shovel, in search of her jewelry box (see photo collage, above).

Photoplay described the inferno: “The fire, which started when a bulldozer hit a rock and showered the dry brush with sparks, was no longer a fire. It was a flock of evil geniuses larking through the drought-dried hills of Hollywood… leaping in great five and ten mile leaps!” A number of actors, already at work on one studio lot or another when they heard about the fire, were instantly panicked. “To understand the panic all these stars felt you must realize that much of the charm of Bel-Air, and its neighboring location, Mandeville Canyon, is their very wildness. They are in the heart of a big city, yet keep so wild that it is nothing unusual for deer to look in a picture window, or an occasional fox go springing over a lawn.” Some of the studios — which, back then, functioned like small municipalities — sent their own firefighters out to help battle the blaze. James Garner tried to drive home, but “cars can vapor-lock in the fiercely generated heat. His car stopped dead. Jim jumped out of the car and left it to burn — then, half-blinded by the smoke, began to run home.”

As Photoplay reported, “there were, of course, some typical Hollywood happenings. For instance, the Red Cross had set up disaster stations, with cots and food. But not one Hollywood person turned up there. Instead, the mink clad refugees piled into the posh Beverly Hills and Beverly Hilton Hotels. Quipped one wag, ‘They were the wealthiest refugees since the Russian Revolution.’ Publicity men were quick to capitalize on the fire. Clients whose homes were not in any immediate danger were urged to pose, hosing down their homes.” When a producer spotted his star in the morning newspaper, “he called his publicity man and bellowed: ‘What good does this do, it doesn’t even mention my new picture!’”

The Bel Air fire blazed for more than three days. Soon after, the third shoe dropped in the form of torrential rains. “The canyon walls, once thickly covered with brush that soaked up excess moisture, were now seared bare. The result: landslides!” (Photoplay, Feb 1962). Some stars whose homes had escaped fire damage, didn’t fare as well with the mudslides: “Tuesday Weld, who spent many months designing and decorating a beautiful home in Laurel Canyon, had her work almost totally destroyed in the recent floods that hit Hollywood. There was three feet of silt in her living room when she came home. Tuesday just turned a key in the lock and checked into the Beverly Hills Hotel. Her friends doubt that she will ever go back to the place” (“Hollywood Today by Snooper,” Motion Picture, May 1962).

Image credits, clockwise from upper left: 1) and 5), Movie Screen Yearbook No. 9, 1962; 2) and 3), Photoplay, Feb 1962; 4) Motion Picture, Feb 1962.

LA just looks like paradise. During one afternoon commute I encountered a wind storm, fallen trees, a giant crane blocking 3 lanes, and a wildfire next to the freeway.

An interesting account!

Scary!

A friend of mine lost her Malibu home to a recent, devastating fire. No small part of the danger to her home lay in its being surrounded by Eucalyptus trees which are highly flammable. It is a tragic reality that California, so tempting a place to call home, is so vulnerable to natures ravages….all too often aided and abetted by human carelessness,

Interesting article, excellently written and researched as we have come to expect from this delightful blog. Great reminder that we must not take healthy climate for granted!

Fascinating read that definitely resonated. Echoes your previous posts on seeing movie stars as both regular folks and demigods.