The two greatest sins in midcentury Hollywood cannot be found in the Old Testament. The studios, abetted by the press, regularly covered up all manner of bad, even illegal star behavior — but two cardinal sins always rated public attention: “going Hollywood” and abandoning Hollywood.

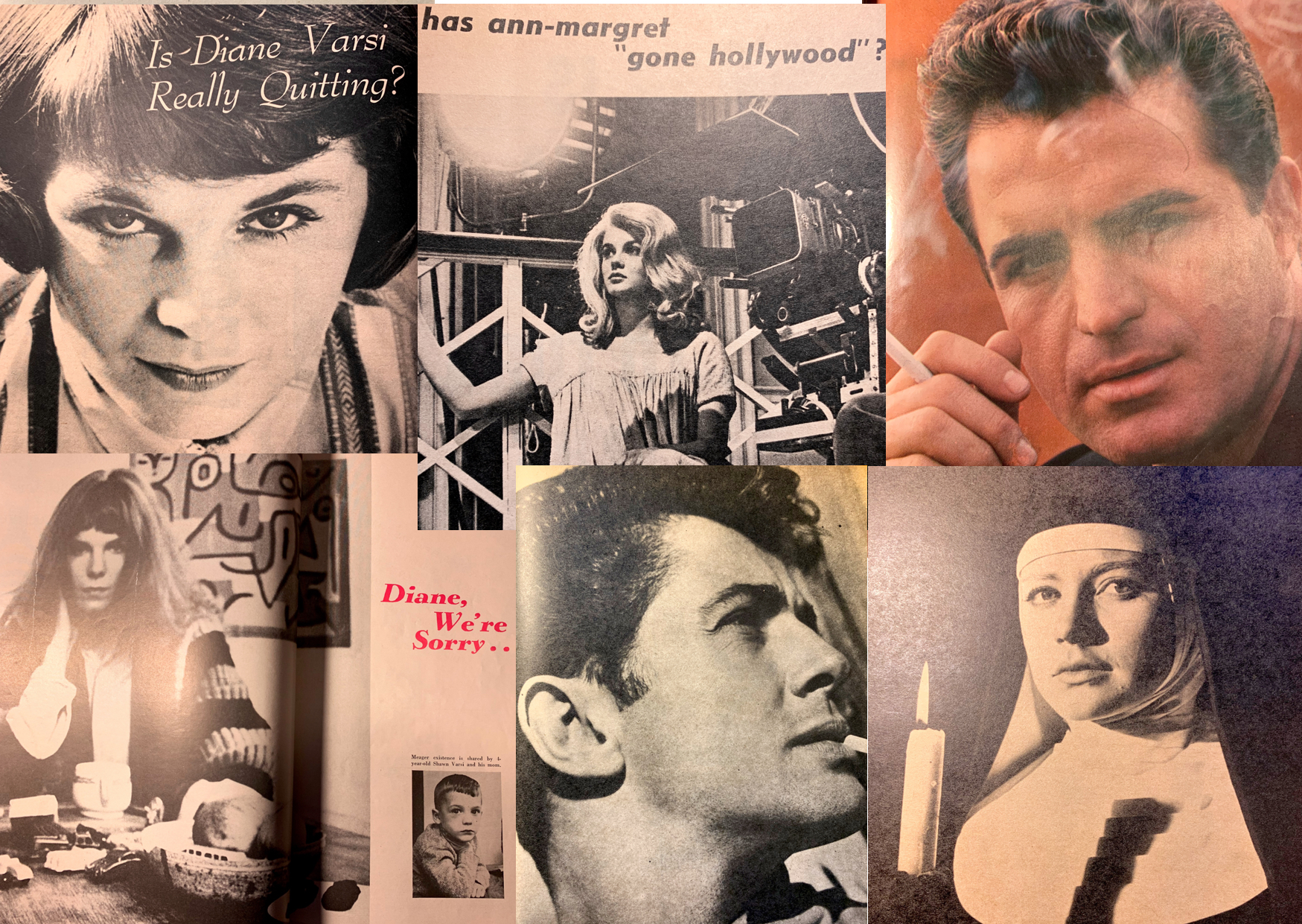

Reporter Jane Wilkie (Confessions of an Ex-Fan Magazine Writer, 1981) explained the former: “Stars were assured they were Special People, glorious thoroughbreds who were glamorous, kind, clean and brilliant, and who were never, never naughty. Some believed the flattery, resulting in the mental illness known as going Hollywood.” Fan mag pundits criticized those who fell too hard for their own hype, as in this item, “Has Ann-Margret Gone Hollywood?” (Modern Screen’s Hollywood Yearbook No. 8, 1965): “1964 was the year her roles got fatter and her head got bigger. [But] one reporter claims that when she takes off her pony tail (to wash it) her head isn’t nearly as big any more.” Many stars themselves disdained the phenomenon as well. Even after winning an Oscar, for example, Shirley Jones told Silver Screen (Oct 1961) that she refused to “go Hollywood. I won’t walk a leopard on a leash or bathe in cherries jubilee.”

Tinseltown’s publicity machine had a continuum of correctives for going Hollywood, starting with (often studio-planted) feature and gossip column warnings, like this one from Rona Barrett (Motion Picture, Jan 1963): “Vince has gotten big-headed and decided he doesn’t want any more fan mag publicity. Anyone remember that just three years ago, no one wanted the time of day from Vince Edwards?” Or this from “Snooper” (Movie Tattler, March 1964): “Steve McQueen is convinced he’s a big enough star to ignore the press. Steve, Baby, nobody’s that big…” If such warnings weren’t enough, there was always the Sour Apple Award bestowed by the Hollywood women’s press corps on the year’s “least cooperative” actor and actress. Winners during the Fifties and Sixties included, natch, the aforementioned Ann-Margret, Elvis, Dale Robertson, Natalie Wood (the year of her traumatic split from Robert Wagner), even Doris Day.

If a star still failed to come to attention — and if his or her hubris spilled onto the set — the next line of attack was to go negative. In the studio era, bad press rarely happened without the studio’s explicit sanction… or active instigation. So, in an item like this one from columnist Sheilah Graham, the “friend” who’s cited is very likely a studio flak in disguise: “Vince Edwards has been getting difficult on the set of ‘Ben Casey.’ A friend of mine who appeared on one of his shows told me that frequently Vince does not know his lines and that he is not very friendly except with his two shadows, a small prizefighter and his stand-in” (Silver Screen, Aug 1963).

Edwards, it seems, really managed to get under his studio’s skin — “fighting tooth and nail over his compensation” for his role as Ben Casey (“Snooper,” Motion Picture, July 1962) surely played a part — because the fan mags began running the sorts of negative reports that usually surfaced only as “blind” items (i.e., no names mentioned). Both of the biggest-name mags, Photoplay and Motion Picture, ran features expressing alarm at Edwards’ fondness for the racetrack. “Vince Edwards’ Secret Vice” (Motion Picture, Dec 1962) opens with the lines, “Gambling. It’s in his blood.” The article quotes an unnamed “Hollywood observer” who describes Edwards’ gambling as “a compulsive thing” that could end badly, in penury or, worse, suicide. The feature’s author further notes that, “of those I talked to, not a single person who had known him since he first came to Hollywood had a nice thing to say about him. And an astonishing number of those associated with him now hate his guts.”

Finally, there was the ultimate corrective. Even worse than negative publicity was no publicity at all, a.k.a. the dreaded “iron curtain” (Marilyn Beck, TV and Movie Screen, Sep 1963), described thusly by “Snooper” (Motion Picture, Nov 1962): “The Hollywood press gets a mad on for an actor or actress every once in a while and, en masse, they level on the unhappy victim to his or her eternal distress. Currently, it is Ann-Margret. Photogs are turning their lenses the other way now when the girl shows up, and there seems to be some sort of pact between columnists not to mention Ann-Margret unless she is hit by a truck or something. This may seem like harsh punishment for what they feel is arrogance, but no star in the early stages of a career can survive without the full cooperation of the press and camera boys.”

For the sin of abandoning Hollywood, however, there was no sure-fire corrective — and, unlike its opposite, which the studios and press understood all too well, the act of turning one’s back on Tinseltown’s glitter and glory seemed not merely transgressive but mystifying. To understand why anyone would voluntarily decide “to leave behind the fame and fortune that was hers for the asking — things which almost every girl would want” (Modern Screen’s Hollywood Yearbook No. 7, 1964), the Hollywood establishment searched for extreme answers. With Dolores Hart, who left acting for a nunnery, they highlighted childhood trauma: “By the time she was eight, she’d seen — and heard — her mother and father quarrel, divorce and remarry three times. ‘I felt completely alone,’ she remembered later. ‘Sometimes I would think that I belonged to nobody.’ Later, living with her grandparents in Chicago, the ritual of the [Catholic] Church was comforting to her small, troubled heart. At 11, she joined the Church and when she was a senior in high school, she made the first of her yearly retreats to a convent” (“Now She Belongs to God,” Modern Screen’s Hollywood Yearbook No. 7, 1964).

With Diane Varsi, whose screen debut in the film Peyton Place (1957) made a spectacular splash and netted Varsi an Oscar nomination, the reaction was more damning. (Midcentury Hollywood, which proclaimed its piety loudly and often, would never go so far as to criticize a nun.) After all, “Diane Varsi had come to Hollywood of her own accord. No one had forced her. No one had discovered her. She came and she made the rounds and she studied, looking for an opening, hoping for a break. And she was one of the lucky ones!” (Movie World, Nov 1961). From 1959, when Varsi left Hollywood to make a new life in New England, through 1961, when she remarried and moved to San Francisco, both fan mag features and gossip items indulged in ongoing debate — did she really leave or was it all a publicity stunt? will she return? when? how? — and psychological analysis. Motion Picture (July 1961) went so far as to publish an open letter to Varsi, titled, “Diane We’re Sorry…” “…that we ever saw those recent photographs of you. We were haunted, frightened and disturbed by your death-in-life pallor, your hopeless, helpless eyes, the set, grim expression around your mouth. We want to reach out, to grasp your hand, to try to lead you back to the world of human beings. Diane, we’re sorry that the strongest emotion in your life is fear. The same fear that brought you to a nervous breakdown when you were filming Ten North Frederick. Diane, we’re sorry that you won’t let us help you. We know you write poetry and are undoubtedly familiar with A. E. Houseman’s line, ‘I, a stranger and afraid, in a world I never made.’”

Varsi did, in fact, return, though not before Hollywood had long since lost interest in her case. It was a rare missed opportunity: Few things seemed to delight the press more than commenting on a star’s attempt at reversing course, as witnessed by these items about Farley Granger, star of Hitchcock’s classic Strangers on a Train: “For several years Farley has given Hollywood the brush-off and he has been finding out that a comeback is often much more difficult than starting a new career. A movie star, to stay on top of the heap, must live in Hollywood, be a part of the community, and get his picture and name in the newspaper and magazines as often as possible. We hear Farley still intends to live in New York City and commute to the coast. If he does, he’ll find the going rougher than he has anticipated” (“Passing Parade,” Movie Stars Parade, March 1956). That’s because, as another columnist (Movieland, Nov 1955) pointed out, “there’s always a newcomer to take the place of somebody who wants to step out. And Farl stepped out — by choice.”

Image credits, clockwise from upper left: (1) Movieland and TV Time July 1959; (2) Modern Screen’s Hollywood Yearbook No. 8, 1965; (3) Motion Picture Apr 1962; (4) Modern Screen’s Hollywood Yearbook No. 7, 1964; (5) Screen Stories Apr 1963; (6) Motion Picture July 1961.

Thanks for the vivid account of Hollywood press behavior. Did the studios invest heavily to control the spin?

The studios didn’t have to invest $$; rather, they manipulated their symbiotic relationship with the Hollywood press. Until the culture as well as Hollywood’s infrastructure changed significantly (through the ‘50s and into the ‘60s), both the studios and the press benefited from suppressing negative stories — unless they were used strategically, as with Vince Edwards in the blog example. If anyone from the press rebelled, the studio could cut off their access to stars and stories.

I can’t help but think that not much has really changed!